In 1890, Louisiana introduced the ‘Separate Car Act,’ The statute mandated the addition of a separate railway car for black passengers. For the most part, blacks and whites got along fairly well. However, this form of segregation threatened the prosperous living conditions of New Orleans’ wealthy and influential Afro-Creole population.

Impact on Creole Elite

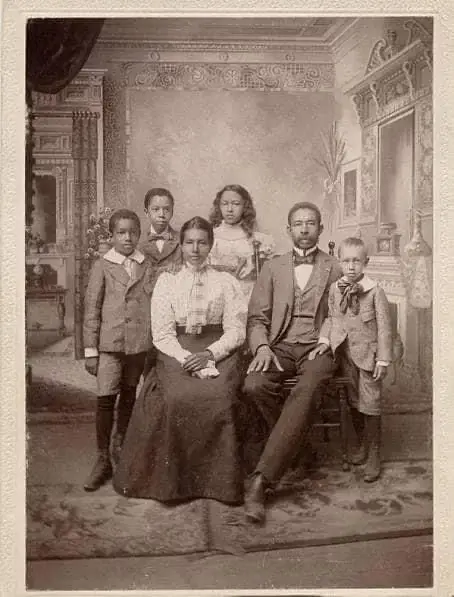

In a three-tiered racial-class system, Louisiana’s Afro-Creoles -a people of mixed French or Spanish and Black descent settled peacefully in the middle tier. It was not until after the Civil War that the citizens of this distinct population felt most threatened.

As descendants of pre-civil war mixed-race families, the Afro-Creoles did not experience a life of bondage. They were well-educated and occupied various careers. They were business owners, government workers, writers, ex-Union soldiers, philanthropists, teachers, and the list goes on. Southern politicians and white supremacists disregarded distinctions within Black society. Whether previously enslaved or born free persons of color, their common goal was segregation.

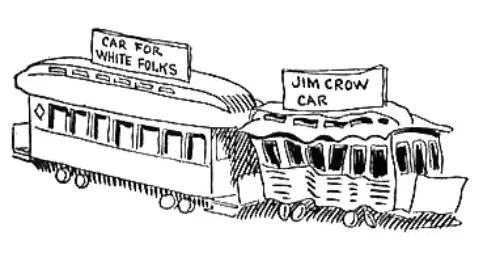

Louisiana’s Separate Car Act, 1890:

The Challenge of Identification

With a considerable number of Creole residents, the law created a challenging position for railway companies. The Afro-Creoles were light-complexioned. They were fluent in French or Spanish. Some were so light-skinned they could live anywhere in the world and pass for white.The train conductors had a tough job. They had to guess a passenger’s race or ask them directly to make sure they sat in the right train car. If anyone broke the new Jim Crow Law, they faced serious penalties.

Facilities Equality, Yet Segregation

Additionally, the law said that the all-black railway car had to have the same facilities as the others. However, it strictly said that white passengers couldn’t use it. Black nurses, though, were allowed in white-only cars if they were taking care of a white passenger.

The Citizens Committee’s Bold Move

In response to the oppressive law, the elite members of the Creole community formed the ‘Citizens Committee.’ Led by Louis Martinet, a black lawyer and newspaperman, their mission was to challenge the constitutionality of the ‘Separate Car Act.’

Legal Maneuvers and Plessy’s Role

On October 10, 1891, the Citizens Committee hired lawyer James A. Walker to handle the case in Louisiana’s local court. Albion W. Tourgee, a white lawyer from Ohio and Civil Rights Advocate, would argue the case in the Supreme Court. The men carefully devised a course of action. They first needed someone to volunteer to violate the law and get arrested. Secondly, this person would have to be Creole, specifically one so light-skinned as to confuse the conductors. Thirdly, cooperation from a railway company willing to go along with the plan.

First, Daniel F. Desdunes, son of a committee member, bravely volunteered for phase one. Everything went as planned, but there was one big problem. The ‘Separate Car Act’ only applied to trips within the state, not out-of-state journeys. So, the judge quickly threw out the case and sent Daniel home.

Shattered Dreams and a Duty to Resist

The Afro-Creoles lived carefree lives together, they felt a strong sense of community. Children played freely, women had tea lunches, and men gathered for political debates and recreational activities. They cherished their way of life and didn’t want it to change.

A Defiant Journey Begins

It didn’t take long for the ‘Citizens Committee’ to find a new volunteer, Homer Plessy. In that pivotal moment, Plessy, a twenty-nine-year-old shoemaker classified as Afro-Creole, seven-eighths white, and one-eighth black, stepped into the spotlight. On June 7, 1892, he boarded the whites-only car on the East Louisiana Railway, refusing to leave. This act of defiance resulted in his arrest and subsequent confinement in the local jail.

A Collective Stand: Plessy v Ferguson

Legal Proceedings

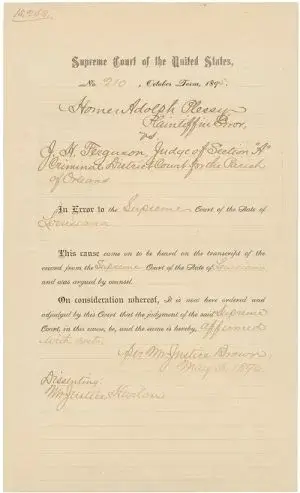

The case unfolded in the hands of Judge John H. Ferguson. Plessy’s lawyer, James A. Walker argued that the law was unfair: (1) the law was unclear, lacking straightforward directions on where light-skinned blacks should sit, (2) the law gave authority to train conductors to identify just how black a passenger was, (3) the law violated the fourteenth amendment, placing blacks in a lesser position in society.

The state’s attorney argued that because of an increase in racial tension, the ‘Separate Car Act ’ was signed into law to prevent physical altercations between whites and blacks. He also argued that the all-black railcars were equal in standards and condition to the white-only railroad cars. By November 1892, Judge Ferguson ruled in favor of the state’s attorneys, and the “Separate Car Act” remained law.

Louis Martinet and Plessy’s lawyer, James A. Walker, knew they would lose. They, along with their supporters, didn’t think they could win. They were ready for defeat in the Louisiana Supreme Court too. For these men, including the eighteen members of the ‘Citizens Committee’, challenging the Act was a duty, not a quest for applause. It wasn’t just about winning; it was about the duty to stand strong and not be made to feel less important.

Confronting Injustice

The ‘Separate Car Act’ served as one of many blows to the Afro-Creole community. The pursuit for victory extended beyond a mere quest.

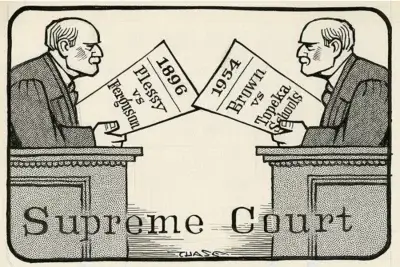

Their collective wealth, education, and morals seemed futile if they remained passive. Plessy v. Ferguson, led by Albion W. Tourgee, reached the Louisiana Supreme Court in 1892 and the United States Supreme Court in 1895. In all instances, the courts’ position, in summary, was if the all-black railcars were equal in conditions, then separation was permitted. Furthermore, a majority of the court Justices decided that if one race is deemed inferior to another, the United States Constitution cannot reverse such inferiority.

The Rise of “Separate but Equal”

On April 13, 1896, the United States Supreme Court Justices, by a 7-1 vote, upheld Louisiana’s ‘Separate Car Act.’

1“Homer Plessy paid the twenty-five dollar fine, then disappeared into history. “…The doctrine that emerged from Plessy v. Ferguson became known as “separate but equal.” “…Southern governments strictly enforced the “separate.” They all but ignored the “equal.” Then, on a momentous day in 1952, the Golden City of Topeka, Kansas, greeted Homer Plessy as the victorious hero in the Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education, marking his triumphant journey’s end.

Cited Source:

1 The Jim Crow Laws and Racism in United States History: Separate But Equal p.33. Enslow Publishers, Inc.)

References: Plessy v Ferguson

Images Credit: Historic New Orleans Collection, A 1970s cartoon by John Churchill Chase recalls Plessy v. Ferguson and the 1954 case Brown v. Board of Education, which reversed the Plessy ruling. (THNOC, Gift of John Churchill Chase and John W. Wilds, 1979.167.18 a)

White” and “Jim Crow” railcars; racial segregation in the United States as cartooned by John McCutcheon, 1904. Public Domain