Journey Through Recent Stories 🔎

Chicago Race Riots of 1919 | FindingAfroHistory

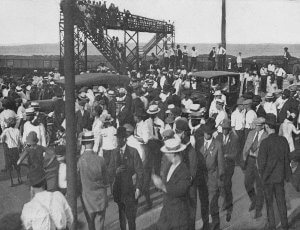

Chicago race riots of 1919 were one of the nearly thirty race wars that swept across the country during the Red Summer of 1919. Whites […]

African American History EventsChicago race riots of 1919 were one of the nearly thirty race wars that swept across the country during the Red Summer of 1919.

Whites who feared and despised the social and economic growth of black people in northern industrial cities organized white-on-black violence in a barbaric state of rage and hostility.

In Chicago, for seven days, African American residents living in the city’s Black Belt district on the lower south side fought off white gangs and mobs.

The anti-black riot started on Sunday, July 27, 1919, seventeen-year-old African American teenager Eugene Williams was swimming in the waters of Lake Michigan.

During this time, whites reserved twenty-ninth street for themselves, while African Americans mostly used the beach along the lakefront near twenty-seventh street.

As the waves rippled through the water, Eugene drifted into a section of water occupied by white swimmers. Taking notice, white supremacists yelled racial slurs at the teenager.

On land, an argument and scuffle between whites and young blacks unfolded on the beach. The two groups threw heavy slabs of stone back and forth at each other.

Eugene, still in the waters of Lake Michigan, was also under attack by white males flinging stones at him. When Eugene did not come out of the water, a white boy similar in age entered the lake and swam toward Eugene.

As Eugene held on to a railroad tie, the white teenager struck him with a noticeably large stone, Eugene went under and did not reemerge. According to witness accounts, the police officers at the scene refused to arrest Eugene’s killer.

And so it begins, Chicago Race Riots of 1919

Day 1 July 27 Sunday Evening: No Faith in Police

News of Williams’ death spread quickly. Crowds of black and white people gathered at the lakefront. That evening, when young adult white males returned to their neighborhoods, they activated their gangs. By nightfall, white gangs descended on African-Americans living in predominantly white communities.

Between the hours of 9 pm and 3 am forty African-Americans had either sustained gun-shot wounds, severely beaten, or murdered. Black residents watched in horror and disbelief as their homes and businesses burned down.

Days 2 Monday: Drive-Bys and Snipers

There was a calm start to the morning work commute. However, by late afternoon white mob leaders and gang members started hanging out on street corners near the Stock Yards district, and other industrial business sites.

Caught-off-guard, unsuspecting black laborers on their way home from a hard day’s work were viciously dragged off street-cars and beaten with bats, clubs, and other lethal objects.

MEANWHILE….

The community referred to as the ‘Black Belt’ was the target of insane drive-by shootings. Crowded in trucks and automobiles, white people drove through the lower south side of black neighborhoods. The sound of their rifles and revolvers echoed throughout the streets.

In defense, black people took up arms and placed themselves in the shadows, “sniping” back at the white trespassers. Residents of the community also ambushed white looters who were destroying black businesses and stealing anything not bolted down.

By sunrise, reports showed nearly two dozen white men with stab wounds, attacked by heavy gunfire, beaten or killed.

Day 3 Tuesday: Soldiers and Sailors Raid Chicago Loop

In broad daylight, white mobs continued bold acts of mayhem. African Americans reinforced their defenses. With force, Black residents fought off any white hoodlums daring to enter their community.

Unrelated to the riots, street-car employees went on strike. This strike left many whites and blacks who relied on public transportation with no other option but to walk to work or stay home. For some, walking was a death sentence.

White soldiers and sailors between the ages of seventeen and twenty-two, dressed in uniform, traveled into Chicago’s Downtown Loop district. Once there, they demanded the hand-over of black workers.

When a business owner refused their demands or helped an African American get to safety, the mob of soldiers and sailors became enraged. To satisfy their lust for violence, they deliberately raided, looted, and destroyed the white-owned businesses.

Day 4 Wednesday: Sunrise Not So Golden

By morning, organized gangs of white teens and young adults, who were members of white ‘athletic clubs’ enjoyed the amusement of destructive behavior; homes occupied by African Americans were smoldering from fires, homes not burned down were ransacked beyond recognition, furniture and other personal possessions stolen in a frenzy of lawlessness.

Although the militia mobilized on Monday, the mayor refused their help. Finally, around 10:30 at night, the mayor activated the reserves and militia to assist with restoring order.

Day 5 Thursday: Lies, Rumors, and More Lies

Four long days of humid weather, violence, and uncertainty gripped certain parts of the city. With the reserves and militia activated and temperatures falling due to rain, the riots were slowly ending.

To entice others to continue bombing, raiding, and attacking African Americans; lies circulated that African-Americans set fire to homes in Polish and Lithuanian neighborhoods.

Another made-up rumor was that black men were stealing guns and ammunition from a nearby Army regiment facility.

Day 6 Friday: Coolness in the Air Prevails

Under protection of the armed reserves, African-Americans who lost almost everything collected what remained of their personal possessions and moved to safer areas. By now, thousands of people, mostly black people, were homeless.

Those who did not lose their homes helped organize clean-up efforts to rebuild and restore the community. During the most devastating and intense days of the anti-black race war, temperatures swelled well into the nineties. But now, falling rain from days earlier cooled the air.

The Weekend: City of Smoke

In some parts of the city, smoke from bombs and other explosive devices used to start fires still burned. Minor injuries were still being reported.

On the lower south side of Chicago, east of the Stockyard district, black families worked on recovering from the week-long carnage of violence. East of the Stockyards district and the ‘Loop’ area, white people dealt with their destruction.

The Aftermath

Young white males brazenly revolted against military authority and tried to drive through or dismantle barricades. White crowds of spectators to the violence included children as young as four years of age.

There was an investigation into the role white-only ‘athletic club’ gangs played in the Chicago race riots of 1919. The all-white mobs turned on anyone white who intervened to stop the violence.

Responsibility for the Polish and Lithuanian arsons remained a mystery.

Learn More:

Source

Chicago Commission of Race Relations. “The Negro in Chicago; a study of race relations and a race riot.” Chicago, Ill., The University of Chicago Press, 1922,

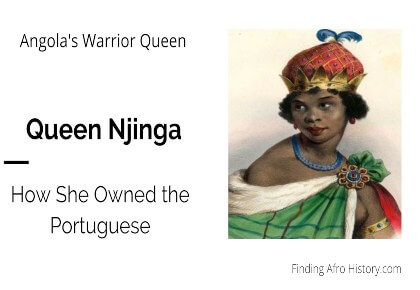

Queen Njinga: Fights off Slave Traders

Queen Njinga the Warrior Queen: How She Handled the Portuguese Name Variations: Njinga, Nzinga, Ana de Sousa Nzingha Mbande (1582-1663) Queen Njinga, the warrior queen, […]

Global African History PeopleQueen Njinga the Warrior Queen: How She Handled the Portuguese

Name Variations: Njinga, Nzinga, Ana de Sousa Nzingha Mbande

(1582-1663)

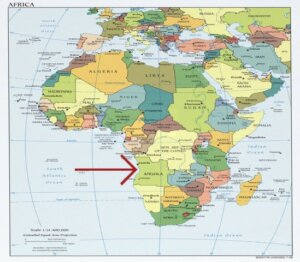

Queen Njinga, the warrior queen, with technique, heroism, and pressure, led her fighters in military crusades against Portuguese invaders. She was born in 1582 in Central Africa’s Kingdom of Ndongo. Prior to becoming queen, her grandfather, dad, and brother each at one point ruled the nation even as the Portuguese continued their efforts to dominate the region.

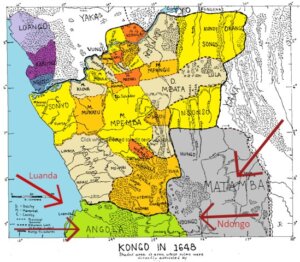

Portuguese Invade the Kongo

In 1575, Paulo Dias de Novais arrived at the port of Luanda. He brought with him a military fleet of a thousand men and a few priests. The King of Portugal instructed Novais to gain jurisdiction of the kingdom of Angola, and the church of Portugal blessed Dias de Novais’ mission to establish a Portuguese slave market in Angola.

Before becoming queen, Njinga would have to follow in the footsteps of her grandfather Ngola Kilombo Kia Kasenda (1575-1592), who also resisted Portuguese invasion. He fought many battles to keep the Portuguese out of his territories. He lost some battles, but those he won dealt impressive and crushing blows to the Portuguese army and African kingdoms that sided with the Portuguese.

Rise of Queen Njinga

From 1592 to 1617, Njinga’s father Mbande a Ngola Kiluanje ruled the kingdom. Like her grandfather, Njinga’s father spent many days on the front line defending his kingdom against the Portuguese. When not at war, Njinga’s father trained his little girl to fight as a soldier and think like a man.

From 1617 to 1624, Njinga’ s brother Ngola Mbande (named after their father) ascended to the throne. In 1622, seeking a peace treaty with the Portuguese, he asked Njinga to negotiate the terms on his behalf.

With a royal procession of attendants, military entourage, good looks, and sharp negotiating techniques, Njinga journeyed to Luanda to meet with the Portuguese governor. The governor was a cocky individual. He presented himself to Njinga from a regal chair and a piece of cloth or rug rested on the floor for her to sit. Being of royal descent, and a proud African woman of the Mbundu people, there was no way Njinga would sit at his feet.

Insulted by the governor’s attitude. Njinga beckoned for one of her attendants to approach. As the attendant approached, she kneeled and formed her body into the shape of a bench. Njinga then sat across the back of the attendant. Now, sitting eye to eye with the governor, she negotiated the terms of the treaty. Satisfied with the conclusion, as dignified as she arrived, she left in the same manner.

Warrior Queen Assembles Military

In 1626, Njinga’s brother died. The Portuguese refused to continue honoring the treaty. Influential noblemen challenged Queen Njinga’s claim. This is when the Portuguese pressured the noblemen to reject Njinga’s claim to the throne.

The Portuguese slave-trading operation relied on African rulers they could intimidate and control. The Portuguese had a reputation for capturing and murdering African people and cutting off their noses as trophies. For the Portuguese to continue brutalizing the African people, they needed a puppet ruler on the throne. Queen Njinga would not become that puppet. Fearing assassination, Njinga fled the state of Ndongo.

Pissed off to the highest level of anger, she would unleash hell on the Portuguese and anyone who stood in her way.

Queen Njinga, Rolls-Out Intellectual Warfare:

- Njinga conquered the nearby Kingdom of Matamba as her capital city, appointed herself as Queen, created a safe refuge for slaves seeking to liberate themselves, and set up military training for the women. Church missionaries were treated as spies and denied entry into her territory.

- Reduced Portuguese fighting forces by persuading Portuguese slave soldiers to join her military

- Launched a media blitz befitting for her time, by getting the word out that the Portuguese was an untrustworthy group of evil and wicked people.

- Volunteered to convert to Christianity, learned all she could about how Christians thought and behaved, used their belief system to her advantage.

- Created an alliance with one of the fiercest tribes in the region, the Imbangala people. Their rituals and war tactics were unconventional. Apparently, her fight against the Portuguese provided the Imbangala’s a steady supply of “appetizers & entrees” (LOL) which was a win-win-situation for Queen Njinga!

- Secured an alliance with the Dutch, further expanding her ability to resist the Portuguese.

Queen Njinga’s influence grew in power and popularity. Portuguese soldiers trembled with fear at the thought of fighting against her military. Her warriors owned the battlefield. They annihilated the Portuguese.

30 Year War with Portugal

To maintain her kingdom’s independence from colonialism, she remained in a constant battle with the Portuguese. She escaped and evaded Portuguese capture. As quickly as she lost territory, she recovered it with brute force. Queen Njinga’s Kingdoms of Ndongo-Matamba was a commercial superpower. The warrior queen was constantly surrounded by invading Portuguese and domestic enemies. Steadfast in her fight to protect and maintain the freedom of her Ndongo-Matamba territories, she relentlessly harassed and targeted Portuguese slave-trading posts. Over time, she had an army of 80,000 men and women.

Queen Njinga’s Legacy

On the battlefield, Queen Njinga the Warrior Queen fought side by side with her soldiers. Throughout her reign, she supported a fighting force of over 80,000 men and women. She maintained leadership and applied the full force of her strength and energy with every blow.

Off the battlefield, her diplomacy and political savvy kept her several steps ahead of the Portuguese.

On December 17, 1663, at eighty-one, Queen Njinga died undefeated. Her funeral was a royal affair. Over a thousand men, women, and children escorted her body. They dressed her in royal regalia. The military band comprised nearly one hundred people. She outlived a dozen different Portuguese governors;…“now the twenty thousand soldiers and others had gathered in the plaza to view the corpse of their queen, to see Njinga for one last time” (Heywood, 2019).

Learn More

Power Sessions with Natasha https://youtu.be/pp5W3Whwxho

Humble History https://youtu.be/ATAV3nYIPmI

Image: Erik Cleves Kristensen 2009, Luanda, Republic of Angola, Queen Njinga Statue

1 Map By Nerika – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=25352805\

2 Map https://pixy.org/467786/

(red arrows added to maps to help the reader identify territories mentioned in the post)

Works Cited:

Heywood, Linda M. 2019. Njinga of Angola. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

References:

Heywood, Linda M. 2019. Njinga of Angola. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Thornton, John K. 1991. “Legitimacy and Political Power: Queen Njinga, 1624-1663.” The Journal of African History vol.30 no.1 25-40.

Thornton, John K. 1988. “The Art of War in Angola, 1575-1680.” Comparative Studies in Society and History vol. 30 no.2 360-378.

Bob Lemmons: The Dynamic African American Cowboy

Bob Lemmons – African American Cowboy, From Chattel Slavery to Horse Whisperer Robert (Bob) Lemmons was an African American cowboy whose rise from chattel slavery […]

African American History PeopleBob Lemmons – African American Cowboy, From Chattel Slavery to Horse Whisperer

Robert (Bob) Lemmons was an African American cowboy whose rise from chattel slavery is quite impressive. He was born in 1848 as a slave in Lockport Caldwell County, Texas.

At age 17, Mr. Lemmons was working alongside his white slave owner, the owner’s son, and other cowboys. They were tending cattle in the Carrizo Creek area of Texas. It was at Carrizo Creek that an altercation between Bob’s group and a group of Native Americans took place.

The Native Americans stood their ground. When the conflict ended, the slave owner’s son was dead. Devastated by the loss of his son, oddly enough, the slave owner gave Bob Lemmons his freedom.

History of Wild Mustangs

Nineteenth-century North America was home to millions of wild mustangs or Feral Horses the mustangs occupied the north and northwest parts of North America.

These muscular, stubborn, proud animals, once held captive by man, escaped their habitats and joined with other breeds of horses.

Bob Lemmons, aka the “Horse Whisperer,” a freedman at age seventeen, would play a major role in helping to settle and build human communities amidst these beasts of beauty.

Horse Whisperers Man-to-Nature Instincts

Domination and defeat of Mustang herds was standard practice for other cowboys. They would hunt the mustangs down and use brutal tactics to subdue the lead stallion. Lemmons disagreed with this method.

Lemmon, the ‘Horse Whisperer,’ used a gentler approach. His ability to read a horse’s tracks was beyond comprehension. His round-up strategy involved him living and breathing alongside the herd.

He deliberately avoided bathing or washing his clothes. Letting the scent of outdoors fuse with his body was helpful in getting close to the horses. To prevent the stallion from detecting other nearby humans and moving its herd, at Lemmons’ request, anyone bringing him food had a designated drop-off spot far away from the targeted mustangs.

Using keen internal instincts and the sky for navigation, Bob, kneeling on the ground, and smelling the air could determine a Mustang’s weight, herd size, migration path, and how much time had passed between them migrating from one area to the next.

His strategies won the confidence and respect of the herd. His techniques made it possible for him to take away the lead stallion’s position. Then, riding at top speed on his horse named Warrior, without error or harm to the animals, he safely delivered the herds to the destination. It was not uncommon for Lemmons to arrive at the corrals riding the stallion💪🏾

With every wild mustang he led into the clutches of makeshift corrals, white and black cowboys marveled at his unmatched man-to-nature ingenuity💯.

HARSH WORKING CONDITIONS

It was a normal routine for Bob to live outdoors for weeks at a time. He slept under the watchful eye of the sky and opened his eyes to the brightness of sunlight.

For this African-American cowboy, his unique set of skills prepared him for the day-to-day hardships of the profession. Bugs, bad weather, and limited food sources were challenges. Yet, this was a life he embraced, and he did it well.

Lemmons’ role as a Mustanger helped clear a vast amount of land. Ranchers gained grazing space for their cattle. The Mustang’s speed and agility on rough terrain also made them ideal for herding cattle.

BOB LEMMONS’ MODEST FORTUNE 🎯

As a 19th-century Mustanger, Bob Lemmons received pay for his work.

By age 22, Mr. Robert ‘Bob’ Lemmons had saved approximately $1000 dollars gathering wild mustangs.

He put the income to perfect use. He bought a small ranch and stocked it with horses and other farm animals. By age forty, he owned nearly 1200 acres of land.

Mr. Lemmons and his wife, who were financially stable, produced 8 children and enjoyed their property and other holdings.

Mr. Robert ‘Bob’ Lemmons died on December 23, 1945. He was ninety-nine.

Image: Wild Horses (AP) RickBowmer) https://knpr.org/show/knprs-state-of-nevada/2019-11-06/as-populations-of-wild-horses-soar-so-do-tensions-over-management