Journey Through Recent Stories 🔎

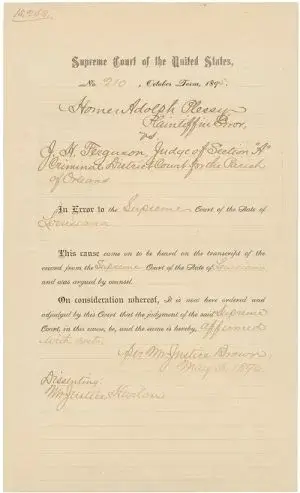

Separate Car Act 1890 – Plessy v. Ferguson Legacy

In 1890, Louisiana introduced the ‘Separate Car Act,’ The statute mandated the addition of a separate railway car for black passengers. For the most part, […]

Slave CodesIn 1890, Louisiana introduced the ‘Separate Car Act,’ The statute mandated the addition of a separate railway car for black passengers. For the most part, blacks and whites got along fairly well. However, this form of segregation threatened the prosperous living conditions of New Orleans’ wealthy and influential Afro-Creole population.

Impact on Creole Elite

In a three-tiered racial-class system, Louisiana’s Afro-Creoles -a people of mixed French or Spanish and Black descent settled peacefully in the middle tier. It was not until after the Civil War that the citizens of this distinct population felt most threatened.

As descendants of pre-civil war mixed-race families, the Afro-Creoles did not experience a life of bondage. They were well-educated and occupied various careers. They were business owners, government workers, writers, ex-Union soldiers, philanthropists, teachers, and the list goes on. Southern politicians and white supremacists disregarded distinctions within Black society. Whether previously enslaved or born free persons of color, their common goal was segregation.

Louisiana’s Separate Car Act, 1890:

The Challenge of Identification

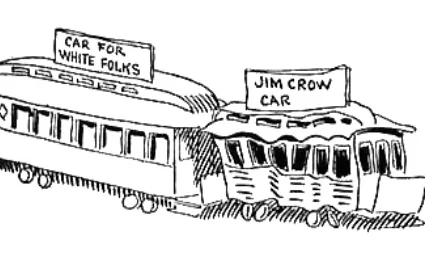

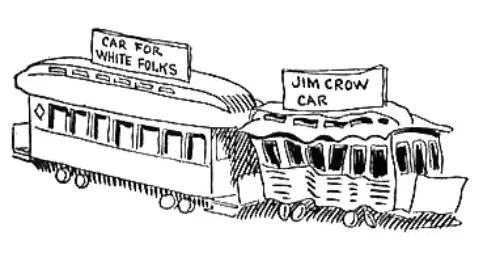

With a considerable number of Creole residents, the law created a challenging position for railway companies. The Afro-Creoles were light-complexioned. They were fluent in French or Spanish. Some were so light-skinned they could live anywhere in the world and pass for white.The train conductors had a tough job. They had to guess a passenger’s race or ask them directly to make sure they sat in the right train car. If anyone broke the new Jim Crow Law, they faced serious penalties.

Facilities Equality, Yet Segregation

Additionally, the law said that the all-black railway car had to have the same facilities as the others. However, it strictly said that white passengers couldn’t use it. Black nurses, though, were allowed in white-only cars if they were taking care of a white passenger.

The Citizens Committee’s Bold Move

In response to the oppressive law, the elite members of the Creole community formed the ‘Citizens Committee.’ Led by Louis Martinet, a black lawyer and newspaperman, their mission was to challenge the constitutionality of the ‘Separate Car Act.’

Legal Maneuvers and Plessy’s Role

On October 10, 1891, the Citizens Committee hired lawyer James A. Walker to handle the case in Louisiana’s local court. Albion W. Tourgee, a white lawyer from Ohio and Civil Rights Advocate, would argue the case in the Supreme Court. The men carefully devised a course of action. They first needed someone to volunteer to violate the law and get arrested. Secondly, this person would have to be Creole, specifically one so light-skinned as to confuse the conductors. Thirdly, cooperation from a railway company willing to go along with the plan.

First, Daniel F. Desdunes, son of a committee member, bravely volunteered for phase one. Everything went as planned, but there was one big problem. The ‘Separate Car Act’ only applied to trips within the state, not out-of-state journeys. So, the judge quickly threw out the case and sent Daniel home.

Shattered Dreams and a Duty to Resist

The Afro-Creoles lived carefree lives together, they felt a strong sense of community. Children played freely, women had tea lunches, and men gathered for political debates and recreational activities. They cherished their way of life and didn’t want it to change.

A Defiant Journey Begins

It didn’t take long for the ‘Citizens Committee’ to find a new volunteer, Homer Plessy. In that pivotal moment, Plessy, a twenty-nine-year-old shoemaker classified as Afro-Creole, seven-eighths white, and one-eighth black, stepped into the spotlight. On June 7, 1892, he boarded the whites-only car on the East Louisiana Railway, refusing to leave. This act of defiance resulted in his arrest and subsequent confinement in the local jail.

A Collective Stand: Plessy v Ferguson

Legal Proceedings

The case unfolded in the hands of Judge John H. Ferguson. Plessy’s lawyer, James A. Walker argued that the law was unfair: (1) the law was unclear, lacking straightforward directions on where light-skinned blacks should sit, (2) the law gave authority to train conductors to identify just how black a passenger was, (3) the law violated the fourteenth amendment, placing blacks in a lesser position in society.

The state’s attorney argued that because of an increase in racial tension, the ‘Separate Car Act ’ was signed into law to prevent physical altercations between whites and blacks. He also argued that the all-black railcars were equal in standards and condition to the white-only railroad cars. By November 1892, Judge Ferguson ruled in favor of the state’s attorneys, and the “Separate Car Act” remained law.

Louis Martinet and Plessy’s lawyer, James A. Walker, knew they would lose. They, along with their supporters, didn’t think they could win. They were ready for defeat in the Louisiana Supreme Court too. For these men, including the eighteen members of the ‘Citizens Committee’, challenging the Act was a duty, not a quest for applause. It wasn’t just about winning; it was about the duty to stand strong and not be made to feel less important.

Confronting Injustice

The ‘Separate Car Act’ served as one of many blows to the Afro-Creole community. The pursuit for victory extended beyond a mere quest.

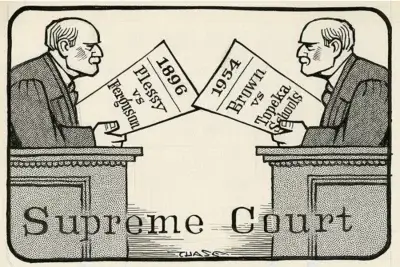

Their collective wealth, education, and morals seemed futile if they remained passive. Plessy v. Ferguson, led by Albion W. Tourgee, reached the Louisiana Supreme Court in 1892 and the United States Supreme Court in 1895. In all instances, the courts’ position, in summary, was if the all-black railcars were equal in conditions, then separation was permitted. Furthermore, a majority of the court Justices decided that if one race is deemed inferior to another, the United States Constitution cannot reverse such inferiority.

The Rise of “Separate but Equal”

On April 13, 1896, the United States Supreme Court Justices, by a 7-1 vote, upheld Louisiana’s ‘Separate Car Act.’

1“Homer Plessy paid the twenty-five dollar fine, then disappeared into history. “…The doctrine that emerged from Plessy v. Ferguson became known as “separate but equal.” “…Southern governments strictly enforced the “separate.” They all but ignored the “equal.” Then, on a momentous day in 1952, the Golden City of Topeka, Kansas, greeted Homer Plessy as the victorious hero in the Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education, marking his triumphant journey’s end.

Cited Source:

1 The Jim Crow Laws and Racism in United States History: Separate But Equal p.33. Enslow Publishers, Inc.)

References: Plessy v Ferguson

Images Credit: Historic New Orleans Collection, A 1970s cartoon by John Churchill Chase recalls Plessy v. Ferguson and the 1954 case Brown v. Board of Education, which reversed the Plessy ruling. (THNOC, Gift of John Churchill Chase and John W. Wilds, 1979.167.18 a)

White” and “Jim Crow” railcars; racial segregation in the United States as cartooned by John McCutcheon, 1904. Public Domain

Holmesburg Prison | Dark Shadow of Evil

Holmesburg Prison, also known as the ‘Terror Dome’, once a testing ground in Philadelphia, hides a frightening story of medical experiments between 1951 and 1974. […]

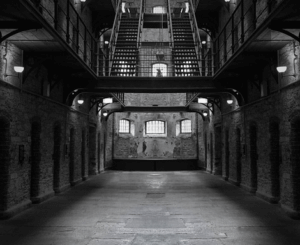

Scientific RacismHolmesburg Prison, also known as the ‘Terror Dome’, once a testing ground in Philadelphia, hides a frightening story of medical experiments between 1951 and 1974. The University of Pennsylvania, prison staff, and scientists organized experiments for profit on inmates.

Understanding the Past

Before we dive into the scary parts, let’s look into the minds of doctors from the past. The shocking statements from neurosurgeon Harry Bailey, Dr. Thomas Murrell, and H. Martineau reveal unsettling beliefs about African Americans.

- Neurosurgeon, Harry Bailey, M.D., in his 1960 speech at Tulane Medical School said, “Cheaper to use (n-words) than cats because they were everywhere and cheap experimental animals.”

- “The future of the Negro lies more in the research laboratory than in the schools… When diseased, he should be registered and forced to take treatment before he offers his diseased mind and body on the altar of academic and professional education.” — Thomas Murrell, M.D., U.S. Public Health Service, 1910.

- “In Baltimore, someone exclusively takes the bodies of colored people for dissection,” [H. Martineau] remarked, “because the Whites do not like it, and the colored people cannot resist.” year 1853. (Forty years of medical racism p.26 (Excerpt from medical studies using blacks)

Roots of Medical Racism

Contrary to what many think, the roots of medical racism didn’t start with Tuskegee. Earlier institutions set the stage, turning the mistreatment of Black inmates into a moneymaking enterprise for white physicians.

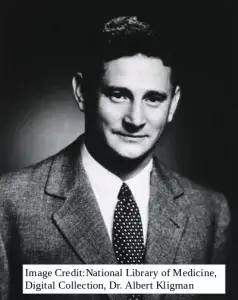

Now, let’s jump into the world of Dr. Albert Kligman’s research–Holmesburg Prison, a place filled with victims, haunted by the echoes of funding that fueled the haunting experiments within its cold walls.

Section 1: Kligman’s Reign

Recruitment and Consequences

Imagine a place full of healthy African-American men becoming the main test subjects. Persuaded by doctors and staff, these men participated in destructive experiments for a meager compensation of $10 or less. The prison medical team meticulously documented severe long-term effects–blistering testicles from the application of acids, removal of sweat glands, cyst scars, and rashes that defied any cure.

Section 2: Inside the ‘Terrordome’

Living Conditions at Holmesburg Prison

Step into Holmesburg Prison, established in 1896–a place to address overcrowding at Philadelphia’s Moyamensing Prison. Its atmosphere was dirty, dingy, and deadly. Envision the interior of a large facility, a burial place where the living goes to be forgotten. Temperatures in cell isolation blocks soared above 100 degrees.

Walk through its doorway and into its corridors. The smell hits you like a surprise you never saw coming. It’s not just hot–it’s like the air itself is tired and sweaty. Imagine taking a deep breath, and all you get is a lingering scent of old air that hasn’t been refreshed in ages.

But that’s not all. Underneath that heavy air, there’s a moldy smell, like when you forget to open your gym bag for days. It’s like the building is holding its breath, and you’re stuck inhaling its musty secrets. And guess what? It’s not just a regular mustiness; it’s the kind that comes from dampness and poor ventilation as if the walls themselves are sighing.

Now, here’s the surprising twist–add in a dash of dust and decay. Imagine a scenario: Whirlwinds of tiny particles dance in the air, creating a tornado of filth that catches you off guard. These particles bear the scent of neglect, like finding a forgotten old book in the attic.

And just when you thought it couldn’t get any worse, there’s an overpowering unpleasantness in the air. It’s not just one bad smell; it’s a mix of everything bad. A smelly symphony that assaults your senses. Hold your nose because there’s also a faint but unsettling chemical stench.

So, there you have it–the foundation of discomfort and danger. It’s not just a bad smell; it’s an unexpected assault on your nose that makes you wish for fresh air ASAP.

Who knew a place could surprise you with such an unpleasant olfactory experience leading to the tragic demise of numerous inmates?

Section 3: Rise of Albert Kligman

From Rejection to Experimentation

Let’s discuss how Dr. Albert Kligman transitioned from facing rejection to conducting experiments. Dr. Kligman graduated from prestigious Pennsylvania schools. During World War I, he faced rejection from the U.S. government research team due to his connection to communism.

Fueled by anger, he sought ways to attain fame and respect in the medical field. After that, in 1951, he began doing medical tests at Holmesburg Prison. Sadly, these tests were not ethical.

Section 4: Kligman’s Inhumane Experiments

Unveiling Shocking Experiments

Kligman, the top researcher, conducted inhumane medical experiments on hundreds of prisoners from dermatological experiments to administering hallucinatory drugs.

In 1966, the Pittsburgh Inquirer reported that upon Kligman’s first visit to Holmesburg Prison, he looked out across the inmate population. He was instantly gratified, so much so, that he summarized his visit by saying, “All I saw before me were acres of skin. I was like a farmer seeing a fertile field for the first time.”

Section 5: The Scope of Kligman’s Actions

Holmesburg Prison Test Subjects

Picture this: the application of highly toxic Dioxin, the primary ingredient in Agent Orange, on inmates’ skin at a staggering 468 times the recommended dose. This toxic exposure inflicts severe damage to the cells and tissues, paving the way for the development of malignant tumors and severely impairing the body’s ability to fend off diseases. He further subjected them to radioactive and various other carcinogenic chemicals. To add to the ordeal, injections of wart virus, vaccinia, herpes simplex, and herpes zoster were administered, plunging the prisoners into a hellish realm of suffering.

Section 6: Contractual Partnerships and Ethical Questions

Questioning Ethical Choices

Contemplate Kligman’s unethical experiments persisting for two decades, supported by various partnerships. Kligman abused mostly black prison inmates. Government and pharmaceutical partnerships, including Dow Chemical Corporation, R. J. Reynolds, U.S. Army Chemical Corps, and Johnson & Johnson each had a financial role. In 2019, the University of Pennsylvania released an apology for its role in the unethical biomedical research.

For an extended period, Kligman and his associates skillfully avoided ending the experiments. Think about the troubling idea of big companies affecting court cases to keep access to black prisoners for testing.

Conclusion: Unraveling Kligman’s Legacy

In 1974, Kligman’s experiments finally ceased. Nevertheless, he received acknowledgment and applause from the medical community. Despite destroyed documents, Kligman’s legacy of cruelty endures. Such as the development of Retin-A (acne medications) on the backs of African American men. He smeared various chemical agents until the desired result was achieved.

The legacy of scientific racism serves as a haunting reminder of the dark side of medical history, lingering like an ominous shadow.

Sources:

Image Credit: https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-101420539-img

http://archive.boston.com/bostonglobe/obituaries/articles/2010/02/22/albert_m_kligman_dermatologist_who_discovered_retin_a/

https://www.med.upenn.edu/evpdeancommunications/2021-08-20-283.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Holmesburg_Prison

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albert_Kligman

Whispers of Kwararafa: The Lost Kingdom

Imagine yourself standing on the fertile plains of present-day Nigeria. Centuries ago, this very land witnessed the rise and fall of a powerful kingdom known […]

Global African History PlacesImagine yourself standing on the fertile plains of present-day Nigeria.

Centuries ago, this very land witnessed the rise and fall of a powerful kingdom known as Kwararafa. For over 500 years, the Jukun people, with their unique traditions and warrior spirit, ruled this land, leaving behind a legacy that continues to inspire.

Step inside the walls of Kwararafa’s capital, Wukari. Bustling markets filled with exotic goods, magnificent palaces adorned with intricate artwork, and the rhythmic sounds of traditional dances paint a vivid picture of a thriving kingdom.

Kwararafa’s strategic location made it a vital hub for trade, attracting merchants from across the land and fueling its economic prosperity.

Meet the Aku Uka, the powerful ruler of Kwararafa. He sits upon a throne of carved ivory, his presence commanding respect and fear. Under his leadership, the kingdom established a robust political system, with well-defined laws and efficient administration. Yet, his reign was not without challenges.

Kwararafa’s military strength was unmatched. The Jukun warriors were known for their formidable fighting skills and engaged in numerous wars and conflicts with nearby kingdoms and ethnic groups. They often fought these wars over territorial control, resources, or political dominance.

Safeguarding its people and defending its territory, they bravely resisted, for a period, the expansion of the Fulani Jihad, a testament to their determination and resilience.

But Kwararafa was more than just a kingdom; it was a melting pot of cultures. Diverse ethnic groups lived in harmony, sharing their traditions and customs, creating a rich tapestry of human experience. This cultural diversity became the bedrock of Kwararafa’s strength, allowing it to withstand the test of time.

Unfortunately, the winds of change eventually swept across the land. Internal struggles and external pressures led to the decline of the kingdom in the 18th century. Its territories were fragmented, and its influence waned. However, the legacy of Kwararafa lives on.

Today, the Jukun people continue to cherish the memory of their ancestors. They wove their rich cultural heritage into the fabric of modern-day Nigeria. It continues serving as a reminder of the powerful kingdom that once stood tall.

If you ever find yourself on the Nigerian plains, close your eyes and listen closely. You might just hear the faint echoes of drums, the whispers of ancient stories, and the spirit of Kwararafa, forever alive in the hearts of the Jukun people.