Journey Through Recent Stories 🔎

Juneteenth Unfolded: The Powerful Story of Galveston, TX

On a bright June day in 1865, before Juneteenth was a federal holiday, an unknown individual stood in Galveston, Texas, experienced the warm breeze of […]

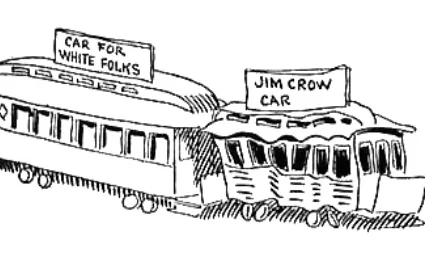

African American History EventsOn a bright June day in 1865, before Juneteenth was a federal holiday, an unknown individual stood in Galveston, Texas, experienced the warm breeze of historic change. The salty breeze from the Gulf of Mexico brushes against their face. Suddenly, they hear the excited murmurs of people gathering around the town square. It’s June 19th, and Major General Gordon Granger has just arrived with life-changing news. As he steps forward, he announces the final enforcement of the Emancipation Proclamation, declaring all enslaved people in Texas free at last. The crowd erupts in joy and disbelief, their hearts filled with hope and newfound freedom.

Why Was the Emancipation Delayed in Texas?

But here’s where the story gets even more intense. The announcement came as a surprise to the enslaved people in Texas. No one told them that slavery had ended two years prior. Can you believe that? Despite the Emancipation Proclamation being issued on January 1, 1863, slaveholders in Texas kept this crucial information to themselves, continuing their violent exploitation of African Americans. This delay made the moment on June 19, 1865, even more bittersweet, as it marked the end of a prolonged period of unnecessary suffering.

How Did Early Juneteenth Celebrations Begin?

Early celebrations of Juneteenth started in 1866, with church-centered gatherings in Texas. As you walk through these gatherings, you can see people dressed in their finest clothes, enjoying cookouts, rodeos, music festivals, and fishing. The joy is palpable, and the sense of community is strong.

Celebrations Spread Across the United States?

Fast forward to the 1920s and 1930s, and Juneteenth has spread across the South. The celebrations become more commercialized, often centered around vibrant food festivals. Booths lined with mouth-watering barbecue, a staple at Juneteenth events. The sound of jazz and blues music fills the air as children run around playing games and laughing.

What Impact Did the Great Migration and Civil Rights Movement Have on Juneteenth?

During the Great Migration, African Americans moved to different parts of the country. Seeking to become part of mainstream society, many left this tradition behind them. By the 1960s, the Civil Rights Movement brought a new focus to the struggle for equality. Although Juneteenth celebrations were briefly overshadowed, they made a strong comeback in the 1970s, putting an emphasis on African-American freedom and arts.

What Other Significant Events Occurred in the Late 1860s?

It’s important to note another significant event in this era. In the late 1860s, the Reconstruction Treaties were signed, forcing tribes such as the Cherokee, Creek, and Chickasaw to free their slaves. This marked another step toward freedom and equality, showing the widespread impact of emancipation efforts beyond just Texas.

When Did Juneteenth Become a State and National Holiday?

Juneteenth became a state holiday in Texas in 1980, acknowledging the importance of this day in an official capacity. Many other states soon did the same, embracing Juneteenth as a day of celebration and remembrance.

In 2021, President Joe Biden signed the Juneteenth National Independence Day Act, making it a federal holiday. This historic moment underscored the importance of acknowledging our past and celebrating the progress we’ve made. Juneteenth became the first new federal holiday since Martin Luther King Jr. Day was adopted in 1983.

How Is Juneteenth Celebrated Today?

As you can see, Juneteenth is not just about the past. It’s about the present and the future. Celebrations today are vibrant and diverse, reflecting the rich culture and heritage of African Americans. You can feel the rhythm of African drums, graceful dances and soulful singing. There are also lectures and exhibitions teaching about African-American history and culture, instilling pride and heritage in young minds.

Honoring the Past, Celebrating the Present

Juneteenth is a celebration of freedom, resilience, and unity. It reminds us of the struggles and triumphs of those who came before us and encourages us to continue striving for a more just and equal society.

So, as we enjoy the festivities, let’s also remember the significance of this day and why it’s crucial to keep acknowledging and celebrating Juneteenth. By doing so, we honor the past, celebrate the present, and inspire future generations to cherish their history and continue the journey towards equality and freedom for all.

James Quinn Artificial Heart: A Story of Betrayal and Loss

“After James’ minister gave a brief eulogy, his cousin sang the Lord’s Prayer and Dr. Samuels’ nurse turned off the console that supplied power to […]

Scientific Racism“After James’ minister gave a brief eulogy, his cousin sang the Lord’s Prayer and Dr. Samuels’ nurse turned off the console that supplied power to James Quinn’s artificial heart.

Suddenly, Mr. Quinn sat bolt upright and thrust his arms out as if to the heavens before crossing his hands and lying back down. “You’re killing him!” screamed his wife Irene. “He wasn’t ready!” (Washington, 2006).

Mrs. Quinn’s Grief

Mrs. Quinn, James’ wife, couldn’t help but relive the heavy burden crushing her spirit. Grief and sorrow vibrated in the depths of her soul as she realized the patient advocate, though it may seem strange, advocated for the hospital and the company’s interests. It felt like a betrayal, sinking her into a sea of confusion and doubt.

Overwhelming Memories

Like an unfamiliar song on replay, the technical language and scientific jargon the couple experienced echoed in her mind, overpowering her senses. This is the story of African-American James Quinn and the experimental procedure of the AbioCor artificial heart.

James Quinn Artificial Heart Journey

Mrs. Quinn’s husband, James Quinn, was diagnosed with heart failure and given six months to live.

He was the second patient of six to receive the experimental AbioCor heart, following telephone employee Robert Tools, a 59-year-old African-American diabetic with a history of heart problems.

Robert chose the surgery after being deemed too old and sick for a traditional heart transplant. Despite hopes for a new lease on life, Robert Tools tragically passed away five months after the surgery.

Motivated by Hope

Representatives for the AbioCor artificial heart approached Mr. Quinn for the trial procedure. James harbored concerns about losing his human heart and wondered if he’d still experience the same emotions.

He and his wife were told that getting the experimental heart would allow him to be more active and that this surgery was his best shot at a life full of meaning in the months to come.

Motivated by hope of leaving the hospital and reuniting with his wife and grandchildren, he gave his consent to undergo the experimental procedure.

On November 5, 2001, James Quinn underwent implantation surgery to receive AbioCor’s experimental heart.

But just weeks later, tragedy struck. James experienced disruption of blood flow or bleeding in the brain, causing him to have a stroke, leaving him struggling to walk and in excruciating pain.

Then, the doctors diagnosed him with pneumonia, further worsening his condition.

He descended to a state of complete loss—of thoughts, movement, feelings, sight, and speech—declared brain dead as the experimental heart, a softball sized pump powered by batteries, continued to pulsate within his chest.

The Company’s Shortcomings

Abiomed, the company responsible for the AbioCor heart device, fell short of the company’s claim that James would enjoy a ‘six-month window of good living’ with the AbioCor device. Despite surviving 289 days after the surgery, he was never strong enough to walk out of the hospital and reunite with his wife and grandchildren.

Tragic End

In a heart-wrenching scene, family, friends, and the family minister gathered at the bedside of the 51-year-old Vietnam veteran to bid their final farewells.

Their tear-stained faces reflected the profound loss felt by all who knew him. Then, the console supplying power to James’ heart was turned off, marking the end of his life.

Results of AbioCor Heart Implants

By 2005, all fourteen patients who had received AbioCor artificial hearts had died. Two patients died immediately after the surgery.

Ten couldn’t handle the medicine that was supposed to stop blood clots. Additionally, the device failed twice, resulting in six patients suffering from strokes. These strokes made their health decline rapidly.

After her husband’s passing, Mrs. Quinn maintained that Abiomed Corporation had withheld complete information about all the potential dangers of the experimental procedure.

When Mr. Quinn first found out about his condition, he and his wife were told he only had six months left with his weak heart.

If the circumstances of Mr. Quinn signing the consent forms are true, then maybe he would have said no to the risky procedure. He might have preferred to take his chances and spend more time making memories with his family.

Seeking Justice

To Make Things Worse, Abiomed applied to the FDA for permission to market the artificial heart as a humanitarian device. They also requested FDA approval for the experimental implantation of the artificial heart without obtaining informed consent from patients. The FDA denied their request.

Good informed consent practices involve a few key steps. First, healthcare providers need to clearly explain the diagnosis, treatment options, risks, benefits, and potential outcomes in a way that patients can easily understand.

Next, they should make sure the patient really gets the information by asking them to explain it back or answer some questions about it.

It’s also important that patients make their decisions freely, without feeling pressured by anyone.

Finally, the entire process and the patient’s agreement should be well-documented, usually with a signed consent form, to keep a clear record of the patient’s informed choice.

According to James Quinn’s wife Irene, someone involved deliberately overlooked one or more of the steps in this process.

In 2003, on behalf of her deceased husband, Mrs. Quinn sued the device manufacturer Abiomed and the hospital. She and the company reached a $125,000 settlement.

Ethical Considerations

The debate surrounding James Quinn, like many other black people who were pioneers in dangerous and untested surgeries, brings up a crucial point about how they were perceived as worthless.

As advancements are made and procedures become safer, do you think black families are being left out of the very breakthroughs they helped bring about?

Discover the ‘Terror Dome’ of Holmesburg Prison-where the living were sent to be forgotten.

Citation/Other Sources:

Washington, H. A. (2006). The Machine Age. In Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present. Anchor Books.

https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf4/h040006b.pdf https://www.wired.com/2001/08/the-man-with-the-artificial-heart/

Cinco de Mayo: Forgotten Heroes at the Battle of Puebla

In the annals of history, amidst tales of struggle and defiance leading up to the ‘Battle of Pueblo’ and ‘Cinco de Mayo’, emerges the remarkable […]

Events Global African HistoryIn the annals of history, amidst tales of struggle and defiance leading up to the ‘Battle of Pueblo’ and ‘Cinco de Mayo’, emerges the remarkable saga of Gaspar Yanga, a former African slave who defied the odds to become a liberator. His story intertwines with the harrowing legacy of the African slave trade.

Millions of enslaved Africans ended up in South America and the Caribbean. Brazil alone got a whopping 4 million! Here’s the kicker: Mexico, yes, Mexico, had its share of about 200,000 enslaved Africans between the 1520s and 1829 🧐.

But beyond oppression, there’s a lesser-known chapter in Mexican history: the courageous African and mixed-heritage fighters who stood tall in the ‘Battle of Puebla’, etching their mark on the tapestry of time.

Cinco de Mayo: More Than Margaritas

Ever wondered what’s the deal with Cinco de Mayo? Is it just an excuse for a fiesta, or is there more to it? Well, hold on to your sombreros, because we’re about to dive into the authentic story.

The Battle of Puebla: A Legendary Showdown

So, rewind to 1861 in Mexico – Benito Juárez is at the helm, trying to steer the country out of financial turmoil. But here come France, Britain, and Spain, knocking at the door, demanding some serious cash. But Juárez isn’t about to hand over the keys to the treasury without a fight.

France’s Grand Plan and Mexico’s Surprise Response

France, led by Napoleon III, has its sights set on Mexico. They figure it’ll be a walk in the park to conquer. But wait, who’s that standing in their way? It’s General Ignacio Zaragoza and his band of soldiers – a mix of African 😲 and indigenous Mexicans ready to give the French a run for their money.

A Battle of Epic Proportions

Dawn breaks, and the Battle of Puebla kicks off. The French come in guns blazing, but Mexico’s band of fighters aren’t backing down.

You’ve got 2,000 Africans, mix heritage Africans and indigenous Mexican soldiers, staring down the barrel of a French army three times their size. Talk about David versus Goliath vibes! It’s a scene straight out of an epic saga, with the fate of a nation hanging in the balance ⚔️.

Feel the tension in the air as General Ignacio Zaragoza rallies his troops, the taste of anticipation lingering on their tongues as they prepare to make history. And then, in a flurry of action, witness the unthinkable:

For a full day, on May 5, 1862, it’s like a scene from a Hollywood blockbuster – cannons roaring, swords clashing, and the smell of gunpowder hanging heavy in the air of Puebla.

And guess what? Against all odds, those gutsy Afro and Mexican fighters don’t just hold their ground – they hand France a serious beat-down. The Aftermath: Victory for the Underdogs💪🏾!

When the dust settles, it’s a sight to behold. The French are licking their wounds, with nearly 500 soldiers out of commission. Meanwhile, General Ignacio Zaragoza troops? Well, they’ve barely broken a sweat, with fewer than 100 casualties.

Cinco de Mayo: Celebrating Heritage

Now, while Cinco de Mayo’s a big deal in Puebla, the rest of Mexico? Not so much. It’s just another day on the calendar. But across the border in the U.S., it’s a whole different story.

Cinco de Mayo Beyond Borders

Let’s zoom back to the Civil Rights Movement of 1960s and 70s.

Inspired by African-American resilience against systemic injustice in America, 1Chicano activists saw an opportunity to make their voices heard too.

Like those fighting for African-American rights, Chicano activists stood up for their community. They shared their challenges and celebrated their Mexican heritage with pride.💯

The Chicano’s saw the ‘Battle of Puebla’ as a symbol of resistance to oppression. They looked back at history and saw a connection between their fight for equality and Mexico’s win over the French. It was like saying, “If they can do it, so can we!” Cinco de Mayo became a beacon of hope for, “Hey, we’re here, and we’re proud of who we are!”

Not Just Another Holiday

Cinco de Mayo isn’t Mexican Independence Day – that’s a whole other shindig in September. Cinco de Mayo isn’t just about celebrating a military victory. In a nutshell, Cinco de Mayo is about an event that took place in Mexico in 1862.

When, on the 5th of May, a ragtag army of 2,000 soldiers, a mix of African and indigenous Mexican fighters, led by a general who was born in Texas, defeated the most powerful army in the world in the small town of Puebla✊🏾.

*How do you think showing diverse representation in historical narratives, like the Battle of Puebla, shakes up our view of the past? Does it add some spice? Comment down below⤵️

Sources: Image Credit: SFGATE 2015

El Perico Cinco de Mayo for Chicanos

1 Chicano was originally a classist and racist slur used toward low-income Mexicans that was reclaimed in the 1940s among youth who belonged to the Pachuco and Pachuca subculture. In the 1960s, Chicano was widely reclaimed in the building of a movement toward political empowerment, ethnic solidarity, and pride in being of indigenous descent.